Towards inclusive leadership and mentoring in research Labs

PI, co-PIs, and project directors can incorporate intentional lab management and mentoring to promote the advancement of women and gender equity. Here, we provide a list of exemplary practices to apply to your research lab. Application of these practices can also benefit other work settings in higher education. We note that the term “trainee” used throughout this section indicates graduates and postdoctoral researchers.

Offering a multi-mentor system: This means having a system of multiple faculty/managers co-mentoring a trainee in the lab. The trainee can be exposed to different research management skills and career trajectories.5, 6 This model of mentoring can increase the trainee’s sense of mastery regarding conducting research and managing the lab by being exposed to different ways of managing research projects. This model can be even more effective for women and women of color to learn from different career development pathways, particularly if there is diversity in the demographics of mentors. This model, however, requires a commitment to recruiting diverse senior and junior-level researchers as lab leaders.7

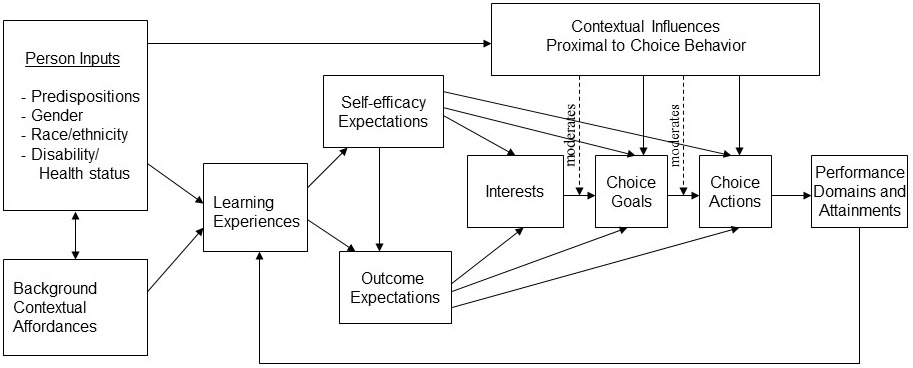

Culturally relevant mentoring: This mentoring practice includes verbally showing an interest in cultural perspectives and approaches to the research, enabling lab members to connect the research project they are working on with their lived experiences, helping them address cultural and demographic variables such as gender, race/ethnicity, and so on. Angela Byars-Winston found that when mentors facilitated culturally aware mentoring in their labs, mentoring rendered greater effectiveness for students with minoritized racial/ethnic identities. The culturally relevant mentoring and lab-management style also enabled women and women of color to perceive a more positive outcome expectation.8 Subsequently, they were affirmed that their ways of knowing would be welcomed and that they would be able to persist and thrive if they remained in the STEM fields.

Encouraging interpersonal interactions in the lab: Do not undervalue the importance of interpersonal interactions in the labs. Those interpersonal interactions among PI, post-doctoral researchers, and graduate students are pivotal in improving lab members' sense of belonging. Dr. Zenda Berrada, chief of the microbial disease laboratory program at the California Department of Public Health, emphasized that lead researchers' ability to engage in interpersonal relationships in the lab helps to develop a good team. Alison Antes, Ph.D., an organizational psychologist at Washington University, has worked on developing lab leadership and management skills training and asserts, “[w]hen you don’t spend much time getting to know lab members as people, it makes it harder to connect about the science itself.“ Of course, a genuine interest, attitude, and willingness to offer resources and support, if needed, should be the starting point. Then, interpersonal relationships can promote a greater sense of social acceptance in the STEM workplace. So, talk about families, children, hobbies, and other personal topics with your lab members whenever possible!