We are around the corner from closing the semester. Many of us may be dashing to complete projects, helping students prepare for finals, getting ready for family gatherings, and so on. The end of the year can be an extremely stressful time for many of us, possibly making us overly self-centered and, thus, more insensitive to others. As a result, we may unwittingly put aside our identities as allies during this time without even realizing it.Nonetheless, this is a crucial time to remind ourselves that inequity never pauses, and we should not let up on our allyship actions. For many women faculty, staff, and students, this time of the year is the most stressful time.1 A survey by the American Psychological Association (APA) showed that end-of-year stress can even put women’s health at risk. To stay strong as allies when our allyship and advocacy are most needed, one effective strategy is to intentionally reflect on your individual allyship goals and actions and to renew your motivations and determinations in this regard. Thus, this Ally Tips will introduce some of the critical questions you can reflect upon at this crucial time of the year.

Reflection Question 1: What does allyship mean to you?

Allies often begin their journey motivated by personal reasons, often because someone they care about shares a story about discrimination. While these are good ally actions, limiting allyship to just helping people you care about reinforces the privileged status of allies as “helpers of the marginalized.” With a little growth, allyship can be less about individuals and more about challenging and resisting the discriminative system that grants disproportionate privilege in the first place. In her reflection on allyship for racial equity, Mary Ann Pitcher, a white woman educator, reflected on this exact discrepancy in allyship and described the shift in her own motivation as an ally in this way: “moving away from understanding racism as the burden of people of color to understanding it as a White people problem.” For Pitcher, then, allyship meant first recognizing her complacency with an educational system and culture that, although unknowingly, still benefitted her and disadvantaged minoritized women and, second, making up for her tacit contributions to inequity.

From this perspective, allyship is a duty and responsibility to give back one’s privilege that came at the expense of others by minoritizing them. What might be some ways in which you can return your privilege/share your privilege? Then, what are the ways to return your privilege to women, women of color, queer individuals, individuals with disabilities, and others with marginalized identities? Here are some questions you can reflect on at this time to finish the year strong as allies.

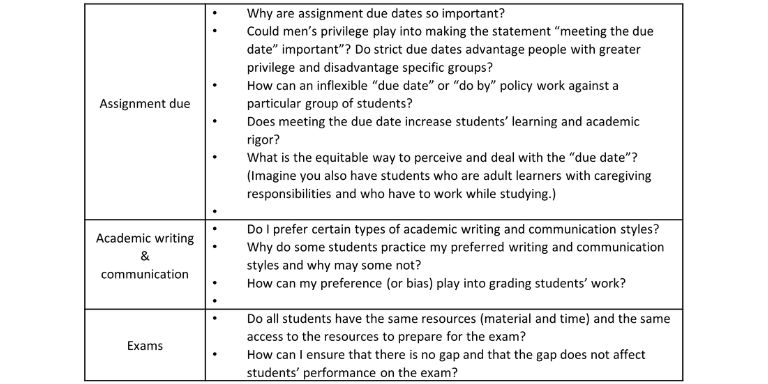

- In the classroom, allies can reflect:

- In the workplace, allies can reflect:

Reflection Question 2: Where do you stand?

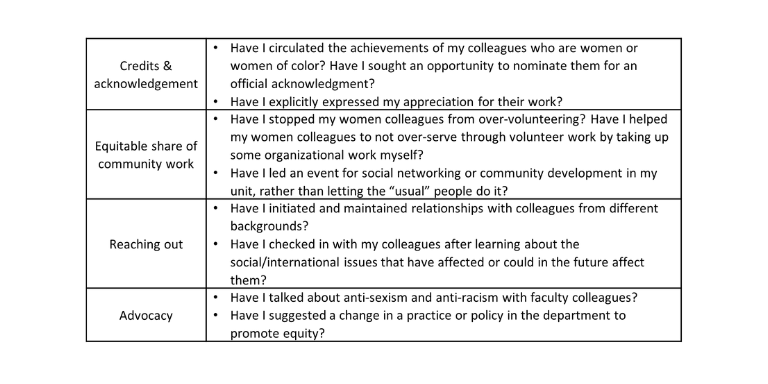

Allyship is a long journey that should involve critical self-reflection. The purpose of reflection is to identify how far you have come and what directions with help you move forward as allies. Andrew M. Ibrahim created this visual mental model (see Figure 1) to keep himself accountable for anti-racism (adopted from a COVID-19 graphic). This graphic describes the stages of becoming anti-racist, which can certainly be applied to stages of becoming anti-sexist or anti-ableist. To move from the “Fear Zone” to the “Learning Zone,”reflecting on the discomfort that stems from having to share the privilege one has had is essential. To move from the “Learning Zone” to the “Growth Zone,” a critical, potentially transformational reflection takes place when one accepts that of accepting one’s unintentional contributions to maintaining the status quo of a discriminative system. You can utilize this graphic to reflect which zone you are in and identify areas for further practice. practice further.

Reflection Question 3: What did not work and worked well when practicing allyship?

As accustomed to the oppressive system as we are, there is much to unlearn and learn as allies. As a result, mistakes are to be expected in allyship. However, constructive allyship can still take place when “you own your mistakes and be proactive in your education.” This means reflecting on what did not work in your practice of allyship and on ways you can improve your skills, confidence, and capacity as allies. This Guide to Allyship offers some follow-up steps for when allies make mistakes. In addition, reflecting on what has worked well in your allyship practice can help you prepare to disseminate your successful and meaningful practices of allyship with dormant/aspirant allies in our midst.

Weekly Resources

Book: White fragility: why it's so hard for White people to talk about racism —This non-fiction book by Robin DiAngelo touches on white people's defensiveness when confronted in conversations around racism. It provides tools to acknowledge and overcome white fragility in realizing racial equity.

Article: (Re)Defining academic rigor: From theory to praxis in college classrooms – Here, Manya Whitaker, a developmental educational psychologist, unpacks the construction of rigor and its misuse.

Article: For women, it’s the most stressful time of the year –This article addresses how women become more burned out during the end-of-year holiday season and suggests ways to have everyone be accountable for making the season joyful and healthy.

Video: We want to do more than survive –In this short, Bettina Love vividly explains the difference between allies and co-conspirators in the fight for justice.