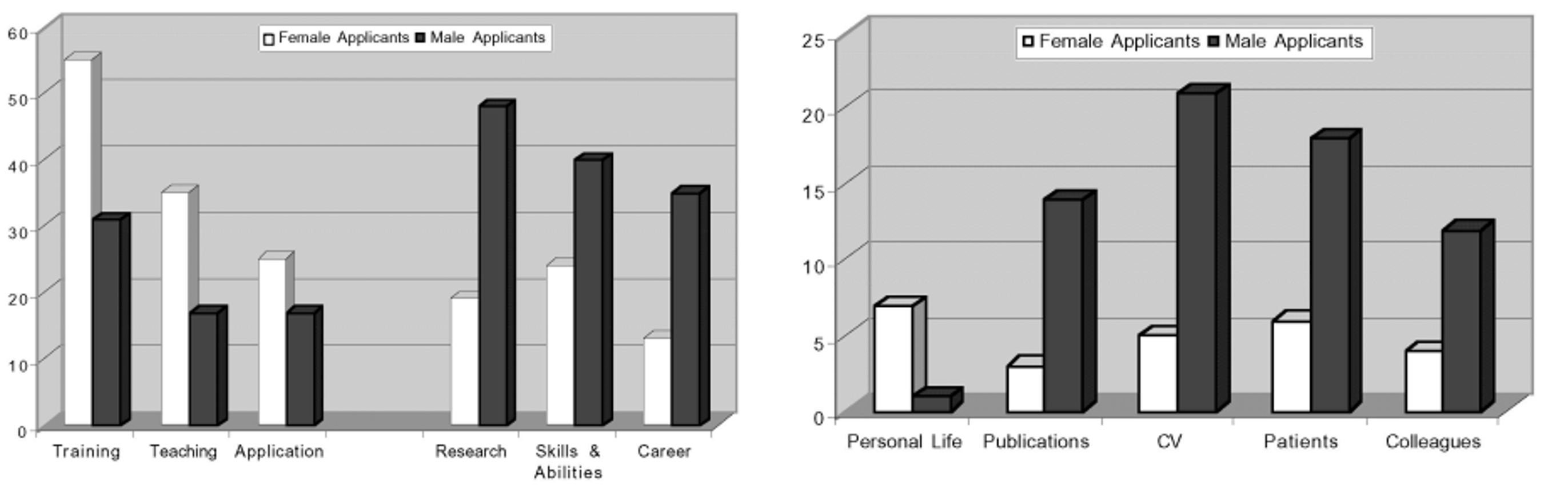

A fundamental act of allyship is recognizing and advocating for the innovative and impactful work of minoritized colleagues, including women. An article published in Nature confirms that women’s contributions are often overlooked, hindering their advancement and retention, especially in fields like science. This pattern of erasure is even more pronounced for women of color, whose foundational contributions in science and the broader society frequently go unrecognized. 1, 2, 3

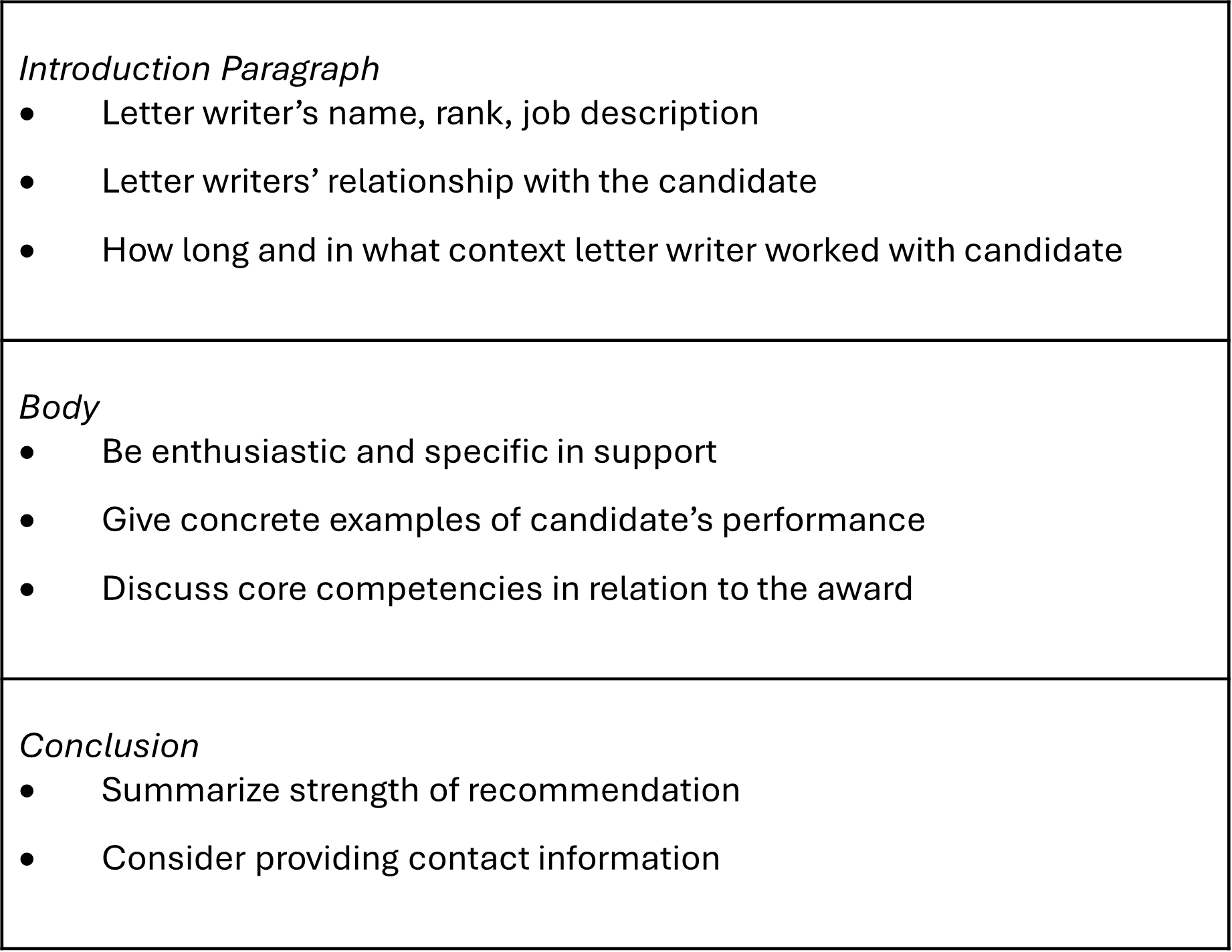

To support gender equity, it is crucial that we highlight and celebrate the achievements of women colleagues. Taking the time to write a nomination letter that acknowledges and spotlights their work is a simple yet powerful action that can help disrupt the cycle of systemic inequity. By ensuring their contributions are visible, we can combat the longstanding erasure of women, particularly those with other minoritized identities. You can find a list of faculty awards for which you can practice nomination of your women colleagues.

This week’s Ally Tips offers practical advice on writing nomination letters that serve to promote gender equity. Join us for our final workshop of the semester, which includes a free lunch, to deepen your understanding of allyship in action.