November is Native American Heritage Month, so we return to our conversation about Indigenous people as one the most underrepresented communities in higher education - particularly Native women. While Native American women make up about 1.1% of the U.S. population, they account for only 0.2% of the U.S faculty body, and 50% of them serve in instructor and clinical faculty positions.1 This disproportionate underrepresentation in faculty ranks is most prevalent for Native women and Hispanic women.2 These groups report various challenges to them as intellectual women, yet they persist and improve our scholarship to address the needs of not only their communities but all communities.3 One specific need of Native American communities healing.4,5 Healing and cure are integral parts of Native American women’s work because, without the process of healing, they remain impaired. They are unable to be the fullest version of themselves due to the traumatic violence that native communities and native women have faced.6 To achieve this state of healing, Native American women scholars have developed innovative research and strategies that depart from Euro-American paradigms for wellness and restorative justice. The scholars’ contributions to indigenous women’s way of knowing have fostered significant advancement in the women’s rights movement in the U.S.—a history that is not often talked about and acknowledged.7 This week, we discuss how higher education recognizes (and erases) Indigenous peoples, Native experiences in higher education, and what you can do to support Native people in higher education. To learn more, check out the First Nation’s Educational & Cultural Center's numerous Indigenous events!

What it means to celebrate Native American Heritage Month

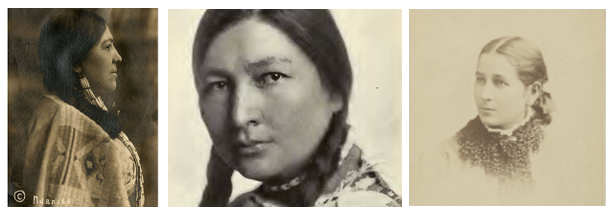

Celebrating Native American heritage is about appreciating indigenous people’s continuous resistance to colonialism, which justified the oppression and genocide of individuals in the name of modern development. It is about immersing ourselves in learning about their creativity and courage, and we should intentionally get to know them. For this sake, here is a very brief list of many Native American women who greatly contributed to the women’s suffrage movement in the U.S. and who we should know: Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Tribe, Zitkala-Sa also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin and the Yankton-Sioux writer, and Susette La Flesche Tibbles, an Omaha lecturer.

By reading through these women’s history, you will note how so many of us have held a deficit view of Indigenous life, one that removes the agency of self-definition from Native peoples and treats them as an “at-risk” community.8 However, it was the oppression through assimilation and erasure of their heritage that caused them to undergo various challenges while also feeling disconnected and guilty of losing their culture.9

Allyship isn’t about reading out land acknowledgments.

An increasingly common practice in higher education and many academic associations is to begin gatherings with acknowledgments, discussing tribal connections to the area upon which the group is meeting.10Although this practice demonstrates progress toward the intended justice, the words in some land acknowledgments often imply that the genocide and forcible removal of Indigenous peoples is a thing of the past; in reality, settler colonialism continues to affect Native tribes, leading to disparities in access to affordable food, housing, healthcare, and education, as well as on-going loss of their culture (like language). Land acknowledgments that only frame Indigenous history and experience as a thing of the past erase the lived reality of Indigenous people and their cultural beliefs about of what “land” truly means.

Action Tips for Allies

No excuse for not sharing works by the Native women: Too often, we make excuses to rationalize our omission of certain peoples in our teaching and research “Oh, there is so much material to cover, and I can’t take all these suggestions.” However, such complacent and privileged excuses have made the Native women in academia invisible. A way to truly celebrate Indigenous heritage and Native women scholars’ contributions is by sharing the voices/works of different Indigenous peoples by regularly and respectfully incorporating Native values into your workplace/classroom.11 Fish and Nyed (2018) offer ideas and examples on how we can do so.

Examine your “Settler Moves to Innocence”: There are many ways in which people currently avoid, distract, or detract from their relationship to settler colonialism. This phenomenon is generally known as settler moves to innocence, which is defined as a settler’s tactic to “relieve the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land or power or privilege.” Tuck and Yang list six ways of such a “move to innocence.” These moves can pop up all over the workplace and in higher education. For example, settler nativism avoids complicity by claiming Native ancestry without any cultural connection (“But I’m 1/16th Cherokee!”). And both colonial equivocation – using the concepts of colonialism/decolonization/etc. vaguely – and free one’s mind and the rest will follow - making no change in one’s behavior following the “decolonization” of one’s mind – attempt to signal a shift in consciousness, but one that does not inherently translate to actions. Tuck and Yang conceptualized these moves to challenge us to question “so what are we actually doing?” which urges us to go beyond exhibiting episodic appreciation of indigenous heritage.

Check your language: There is a lot of language used throughout the workplace that appropriates Indigenous culture. For example, it is common for people to call a gathering “a powwow” or to say that something that is low priority is “low on the totem pole.” You might be tempted to call someone you idolize your “spirit animal” or describe someone acting irrationally as “off the reservation.” These phrases trivialize the cultures and histories of Indigenous people, contributing further to negative stereotypes about the lives of Native people.12 Furthermore, beyond these simple phrases being problematic, try to recognize when you linguistically cast Native people and culture into a mythical/mythological light, as if the culture of Native peoples is a thing of the past or as an exotic, fictional, or lesser-than experience. When we create a mythological narrative around Native people, we functionally reinforce a position that Western ideology and culture are real, legitimate, and sensible.

Weekly Resources

- Book: American Indian stories– Combining Zitkála-Šá’s childhood memories around boarding school, she shares her reflection of the painful price of success which is estranged from her cultural roots and challenges the negative stereotypes of Native American by sharing the stories of her loving family in the reservation.

- Video: Running for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women – Rosalie Fish, a competitive runner from the Muckleshoot Reservation in Auburn, Washington shares her reasons for running. She has become known due to her run with a red hand-prints painted over her mouth to raise awareness about invisibility of Native women, which causes an epidemic of crime against these women.

- Article:Indigenous Perspectives on Native Student Challenges in Higher Education - Robin Zape-tah-hol-ah Minthorn discusses policies/practices in campus offices, classrooms, and beyond, which can honor Native students experiences and cultures in higher education.