October is National Work and Family Month. This observation was established to celebrate working families' achievements and focus on the challenges they face. Achieving a good sense of life-work balance becomes even more difficult for mid-career faculty and middle-level managers. There are various definitions for “mid-career”: for faculty, this typically means in the post-tenure period, with 12-20 years of teaching, research, and service, or in the “middle years” of their life.1, 2 During the mid-career period, women’s attrition is generally greater, and they are more likely to struggle than men to get to full professorship or top leadership positions. One contributing factor is that the time for caregiving for young child(ren) and for aging parents often overlaps with the mid-career period, and those responsibilities usually weigh much heavier on women.3 At the same time, mid-career faculty can also experience post-tenure burnout and an increase in leadership and service responsibilities, which they might not feel prepared for.4 Moreover, the generally lower number of women in leadership and full professor positions makes it harder for mid-career women to find effective mentoring and career networks. Thus, this week, we will discuss ways of supporting mid-career faculty, particularly women.

While enjoying the rest of Ally Tips today, please check out our upcoming workshop on Better Allies and Co-Conspirators for Equity on Campus. Our team will share practical tips for advocating equity in your own contexts.

What Mid-career Women Faculty Experience

After receiving tenure, mid-career women faculty (as well as men) are often expected to take on various leadership and additional service roles. However, research has found that mid-career faculty often feel neglected despite this potential increase in visibility and that this is felt more strongly by women.5 Up to the tenure point, they perceive an investment in them by their unit and the upper administration. Yet, after tenure, women often feel a lack of recognition and that they are left alone to manage their new administrative and leadership roles while navigating the often inequitable distribution of service.6

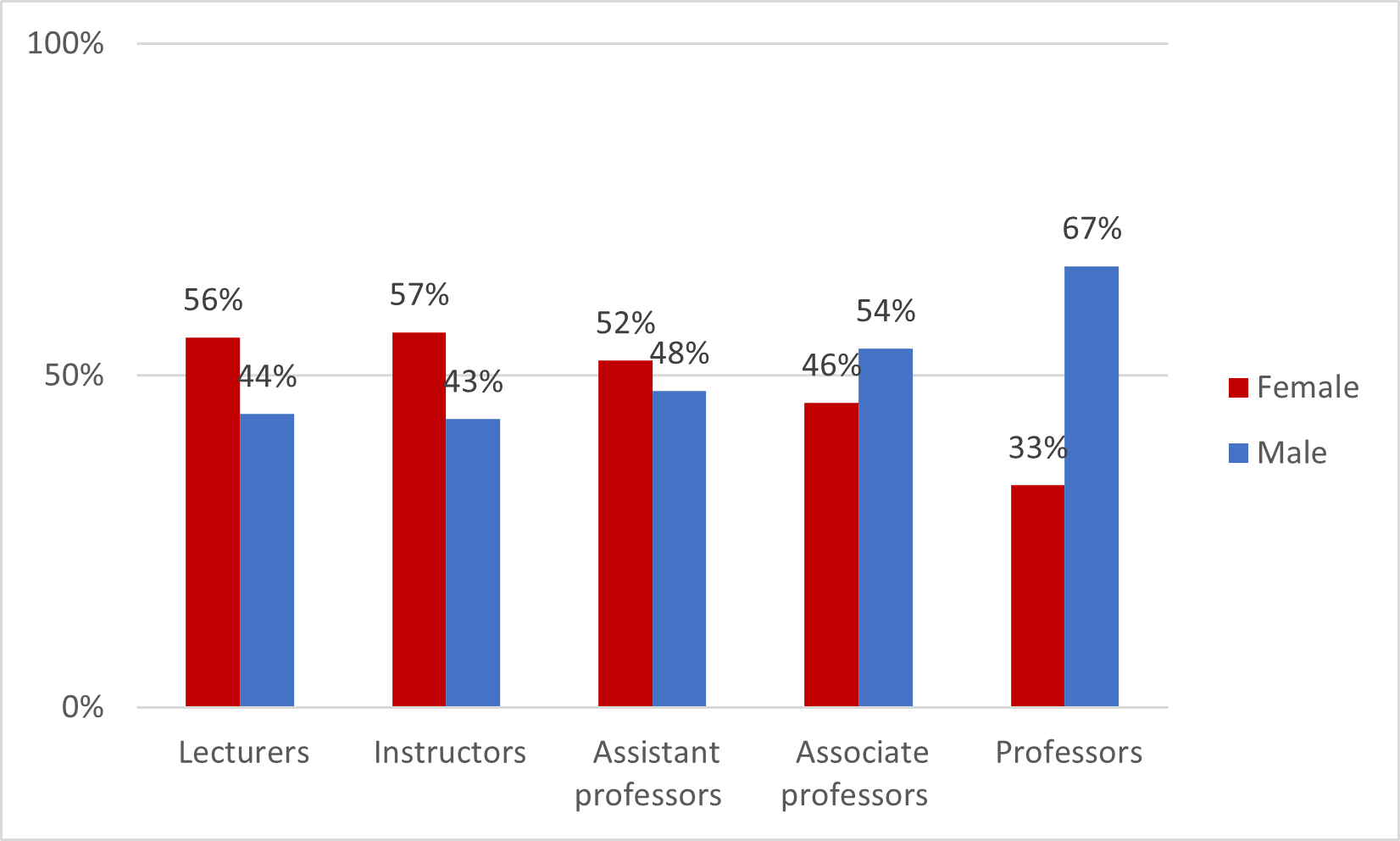

Mid-career, post-tenured faculty undergo job re-crafting.7 For women faculty, however, this process often involves re-evaluating and needing to re-craft their jobs to shift their one-track career-focused minds to a more work-life-balance-oriented mindset. They also tend to pursue the quality of their relationships, whether in their personal lives or with students and colleagues, and either choose or need to spend more time raising their child(ren), taking care of their parents, and managing their own health.8 While mid-career men faculty are also found to increase their shared caregiving responsibilities after obtaining tenure and to experience a similar pattern of job re-crafting like women, women tend to perceive a much greater mismatch between workplace support and their new career and life orientations. As a result, they often have lower job satisfaction.9 Furthermore, the lack of tailored support for mid-career women faculty and the lack of full-professor mentors available to them (see Figure 1) may lead to them spending a more extensive period in the associate rank. This extra time, in turn, may lead to a much lower representation of women in the full professorship. Ultimately, this contributes to the vicious cycle of the gender gap in academia. Importantly, this trend can be further exacerbated among racially minoritized women faculty.

*Figures 1 and 2 wererecreated based on the 2018 faculty data from the National Center for Educational Statistics.

Action Tips for Allies

Advocate for establishing clarity about the post-tenure criteria and review: Something that often makes women’s transition from associate to full professorship is the ambiguity that can exist around certain aspects of the promotion process, particularly in STEM disciplines. A study found that the institutions participating in the NSF-ADVANCE program, which promotes data transparency, awareness, and clarification of all policies and procedures related to post-tenure review, improved women’s representation among the full professor rank and shortened their average time in progressing from associate to full in STEM fields. So, as you read this, even if you feel that post-tenure expectations are clear, as an ally, you can advocate for establishing clearer post-tenure criteria and review procedures or a system for reviewing their clarity. The Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty & Academic Affairs offers various workshops on promotion tailored to post-tenure track faculty. It co-sponsors a mid-career mentoring program (IAS) and a Women in Leadership conversation series.

Being serious about retaining and mentoring women and women of color at the department level: In the 2019Gender and Faculty Satisfaction Report produced by the IUB Campus Assessment Committee on Gender and Faculty Satisfaction, women faculty in associate and full professorships showed the least satisfaction with mentoring experiences with from someone in their department. Conversely, they expressed the highest level of satisfaction with mentoring from someone outside the IUB campus. Although there could be multiple interpretations of this finding, a likely one is that, unlike men, women faculty at IUB are forced by their situations to search for mentoring outside of their department and even their university. Although finding capable mentoring outside one’s institution is valuable, capable mentors within one’s institution are a vital aspect of academic success. Importantly, as the representation of women faculty of color is even more problematic, the issues just mentioned are exacerbated for women faculty of color. Figure 2 shows that women of color are greatly underrepresented in full professoriate nationally (Black women account for 1.1%, Hispanic women, 1%, Asian women, 2%). Considering this on-campus context, we can imagine how hard it is for early mid-career black women faculty to find their mentors within their department. Based on this figure, we can postulate how much harder it may be for racially minoritized women faculty to find an effective mentor who can help them to navigate the double bind of academic discrimination in higher education. To be able to make quality mentoring opportunities available for women faculty of color who are in their mid-career, our campus can be serious about mentorship of future women faculty of color by 1) improving representation by hiring women faculty of color at the full professor rank, by 2) dividing the service burden on senior faculty more equitably across gender and race, thereby freeing senior women faculty and women faculty of color to mentor more; and by 3)developing mentoring programs that help link junior and senior women faculty with similar interests. Examples at IUB are the Faculty-to-Faculty (F2F) Mentoring Program and Enhanced Mentoring Program with Opportunities for Ways to Excel in Research (EMPOWER).

Listen to the familial burdens and health issues of midlife women colleagues and challenge the negative stereotypes and jokes around them: Individuals in midlife, regardless of identities, go through their unique challenges in terms of health. However, health issues prevalent among mid-life women and minoritized individuals are, when compared to men in our society, more often negatively stereotyped and used in jokes. Those stereotypes include but are not limited to “forgetful, over-heated, flustered, unlikable, and cold.” In fact, these are derogative in their nature and void of awareness of the increased familial burdens that mid-career and mid-life women have to take, resulting in exhaustion that wears on the nerves to a greater degree to women and women with minoritized backgrounds. Rather than being listened to, they are also asked to “act nicer, maybe take a pause” at work. Considering the lack of potential mentor pull for the mid-career and mid-life women in academia, it can be substantially challenging for them to navigate such an unsupportive work environment by themselves, without allies. Lastly, reflect on how your power and privilege may insulate you from having to listen, because society convinces us that this topic is unnecessary to talk about, uncomfortable to talk about, and considered a “women’s only” issue.

Weekly Resources

Video: The Link between Menopause and Gender Inequity at Work – Andrea Berchowitz provides practical advice on how to create a menopause-friendly work culture that supports gender equity and diversity retention in the workplace.

Article: Enabling Midcareer Faculty of Color to Thrive – The article addresses the “invisible labors” that faculty of color are expected to do during the mid-career period and experience challenges in advancing to the full professorship.

Article: Agentic but not warm: Age-gender interactions and the consequences of stereotype incongruity perceptions for middle-aged professional women – Jennifer Chatman and her colleagues corroborated how the bias against the middle-aged women is deeply embedded in higher education, affecting the evaluation of those women despite their high performance.

Article:Career Transition to Non-Tenure-Line Faculty: Midlife Women’s Challenges, Supports, and Strategies – Women in academia are represented higher in non-tenure track (NNT) positions. Thus, significant attention to the midlife women in NNT should be paid to broadly impact gender equity for mid-career faculty.

Reports: Assessing faculty satisfaction with IU – Find IUB campus reports on faculty satisfaction assessed with the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education (COACHE) faculty satisfaction survey. Various parameters were used to assess faculty satisfaction by gender, race, and faculty rank.

- Webpage: World Menopause Day – October 18th